The recent accident at Farmgate, where a bearing pad from the metro rail came loose and claimed one life, has raised serious concerns about construction safety and maintenance oversight. That person was Abul Kalam Azad, a commuter from Narayanganj who had simply set out for work that morning.

He never returned.

A component meant to represent progress turned fatal, leaving behind a young wife and two small children. The government announced Tk 5 lakh in compensation and offered a job to a family member, a gesture meant to console but one that instead deepened the family’s grief.

The Farmgate accident has reignited serious concerns about construction safety and maintenance oversight. In Bangladesh, death feels disturbingly omnipresent, lurking in the most ordinary corners of daily life.

No one can tell when or how it might strike. You might leave home for work in the morning only to have your vehicle overturn on a waterlogged street. You might be sitting in traffic when another car crashes into you from behind.

As has happened before, a girder from an ongoing construction project could come crashing down on your vehicle. Even walking, the simplest and seemingly safest act, offers no real safety. Bricks may fall from half-built structures, or, as we see today, a component from an elevated metro rail can suddenly come loose and end a life in an instant.

We hear of such avoidable deaths almost every day. Not long ago, a bus that had stopped to let passengers off after an accident was struck by an oncoming truck, killing several people who had just disembarked.

A few years earlier, a female bank official lost her life when bricks fell from an under-construction building as she was returning home.

In another case, pedestrians were crushed when the main gate of an educational institution under construction collapsed. In 2022, five people were killed when a girder from the Dhaka BRT project fell onto a passing vehicle.

In Bangladesh, the same tragedies keep recurring. Each major accident sparks outrage and official promises, only for attention to fade and the system to slip back into its unsafe routine. The BRT project, for instance, saw a girder collapse in March 2021 that injured four people, including two foreigners.

A year later, another collapse claimed five lives. Now, our metro rail, celebrated as a symbol of modernity and progress, has joined this grim pattern.

On September 18, 2024, around 9:30 am, metro operations between Agargaon and Motijheel came to an abrupt halt after a viaduct bearing pad came loose between Farmgate and Bijoy Sharani.

The component dislodged shortly after a train passed and crashed onto a car below, damaging it severely but miraculously causing no injuries.

Authorities promptly formed an investigation committee, a response that has become almost procedural. But as history shows, such probes rarely lead to lasting lessons or accountability.

Officials called it only the second incident of its kind in global metro rail history, the first occurring in Vietnam in 1986 with fatal consequences, a grim reminder of what could have been.

Subsequent independent searches and AI-assisted reviews, conducted and published by a national daily, reinforced that finding. When asked whether any other metro system had ever reported a bearing pad falling off an operational viaduct, multiple artificial intelligence platforms including ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, and Grok, each confirmed that no such failures had been documented anywhere else. Google searches yielded the same result.

Bangladesh sets a unique example

In effect, Bangladesh now stands as the only country in the world where a metro rail bearing pad has fallen twice, one of which has already proved fatal. This makes the Dhaka incidents not just tragic but globally unique, a distinction no modern transit system should bear.

Experts voiced serious safety concerns following the incident, warning that a potential design flaw might be to blame. They noted that sections of track where trains take sharp turns experience greater stress, requiring additional reinforcement.

In such areas, clamping mechanisms and nut-bolt fixtures are typically used to secure bearing pads and absorb excessive loads. The metro’s design, they argued, had not adequately accounted for this factor. The warnings were clear, but as is often the case, they received little attention.

This recurring negligence among public officials underscores a troubling pattern of disregarding expert advice until crises force a response. Specialists recommended immediate reinforcement of the existing bearings and suggested replacing rubber pads with more durable metal pod bearings to ensure long-term safety.

Following the incident, Dhaka Mass Transit Company Limited (DMTCL) formed a seven-member committee to probe the matter. Its preliminary findings noted that while such bearing pad failures are rare, it could not definitively attribute the cause to a design deficiency. It also proposed installing surveillance cameras to monitor stress loads and traffic flow at critical points.

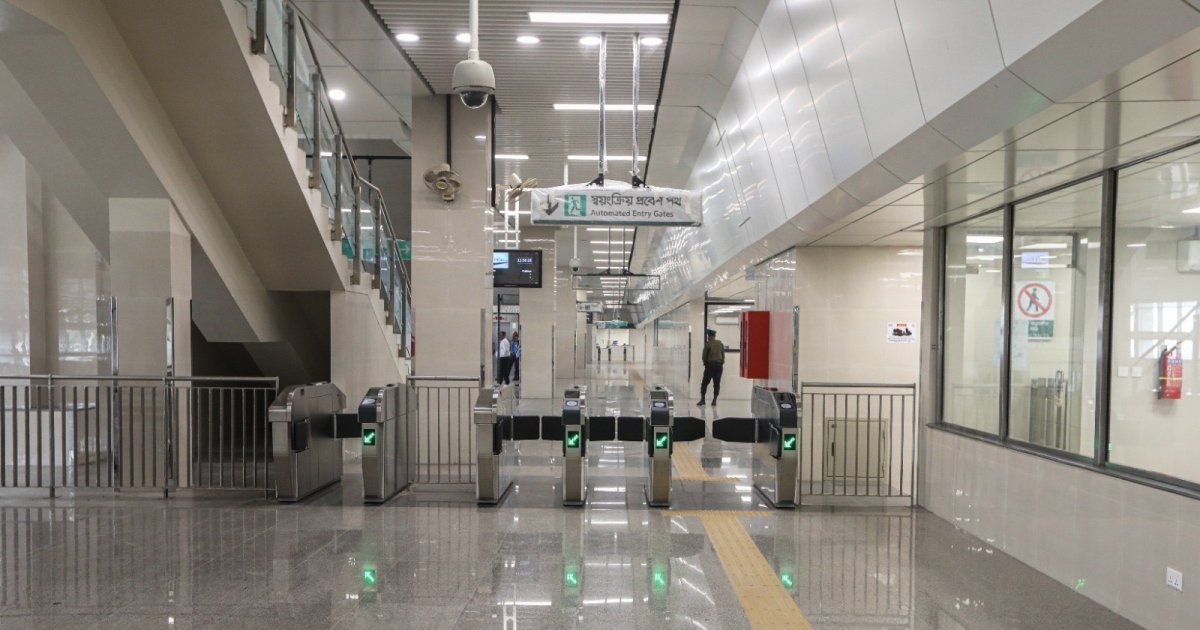

The episode once again placed metro rail safety under scrutiny. The Dhaka Transport Coordination Authority (DTCA) has long known that DMTCL has been operating metro services for nearly two years without the required safety certification. Although DTCA directed the appointment of an independent third party to certify system safety before operations began, that process remains incomplete.

Reports in several national newspapers revealed that DMTCL has been running the metro rail without fulfilling key legal safety requirements. Under the Metro Rail Act 2015 and the Metro rail rules 2016, the company is legally obliged to submit regular safety reports to DTCA and obtain both technical and safety approvals. Yet DTCA officials confirmed that not a single safety report has been submitted since operations began.

Records show that DTCA repeatedly issued letters reminding DMTCL to comply, the most recent reminder coming only months ago. Although discussions were held before the launch on appointing an independent third party for certification, the formal approvals remain pending to this day.

Officials further alleged that DMTCL has yet to secure construction plan approvals from DTCA, approvals that are mandatory under existing law. They claimed that political pressure has obstructed enforcement. Meanwhile, the operating agency has neither insured the metro system nor introduced passenger liability coverage.

There is still no clear framework for compensating victims in the event of an accident caused by mechanical failure. Despite repeated warnings, no corrective action has been taken to address these serious compliance gaps.

Other countries show how safety can be enforced when accountability is non-negotiable. India’s metro projects maintain strong safety records through independent third-party audits and strict oversight from the Commissioner of metro rail safety.

Singapore’s Workplace Safety and Health Act goes further, imposing fines of up to Tk 3.3 crore and jail terms for corporate negligence leading to fatalities. These frameworks reflect an understanding that safety failures are not mere accidents; they are administrative crimes.

When contacted by the press, the then managing director of DMTCL denied that a design flaw had caused the earlier bearing pad incident, saying a detailed investigation was underway. He assured that new systems were being introduced to prevent similar accidents and improve safety.

Safety measures in place

Rauf noted that while the metro had received a safety certificate from the Japanese contractor, an independent third-party certification, legally required, was still pending. He also admitted that DMTCL had yet to submit routine safety reports but promised to start doing so “within the month,” a pledge that now rings hollow after the latest tragedy.

Regarding insurance, he said DMTCL was in talks with the Bangladesh Jiban Bima Corporation to develop a comprehensive insurance and compensation policy. He added that the contractor was liable for technical failures during the two-year defect period and that an emergency response policy would be prepared “in due course.”

Yet before such assurances could materialize, tragedy struck again. A bearing pad at a pillar near Farmgate came loose and fell, this time killing a pedestrian walking below.

This latest incident lays bare the devastating consequences of systemic negligence and institutional inertia. It is the result of a culture of complacency and bureaucratic delay, where coordination failures between government agencies are treated as routine rather than alarming.

The cost, however, is borne by ordinary citizens — people who pay taxes, obey the law, and trust the state to safeguard their lives. Every institution connected to this failure shares responsibility, and silence can no longer be an acceptable response.

The tragedy also exposes how cheaply human life is valued in Bangladesh. In economic terms, countries often use the Value of Statistical Life (VSL), an estimate of how much society is willing to spend to prevent a single death.

For instance, the US Environmental Protection Agency applies a VSL of about $10 million, while in Bangladesh, studies estimate it between $15,000 and $250,000. Yet actual compensations rarely reach even that. When the state pays Tk 5 lakh for a breadwinner’s death, it effectively signals how little value is placed on a citizen’s life.

Beyond demanding exemplary punitive action, we must ask a harder question: Why were the recommendations from previous investigations never implemented, or implemented too late? Until accountability is enforced and safety protocols are treated as non-negotiable, these preventable tragedies will keep repeating, each one a painful reminder of how expensive inaction can be.

The right to commute safely, to work without fear, or to walk beneath a public structure without risking death should not be a privilege reserved for the lucky. The question, “What is the cost of a human life in Bangladesh?” must not have a calculable answer.

A life is priceless, yet our institutions act otherwise. Until those responsible for these preventable deaths face real consequences, the cycle of negligence will continue, and progress will remain fatally fragile.

Nafew Sajed Joy is a Bangladeshi researcher, writer, and environmentalist. He holds Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Social Sciences from the University of Dhaka.