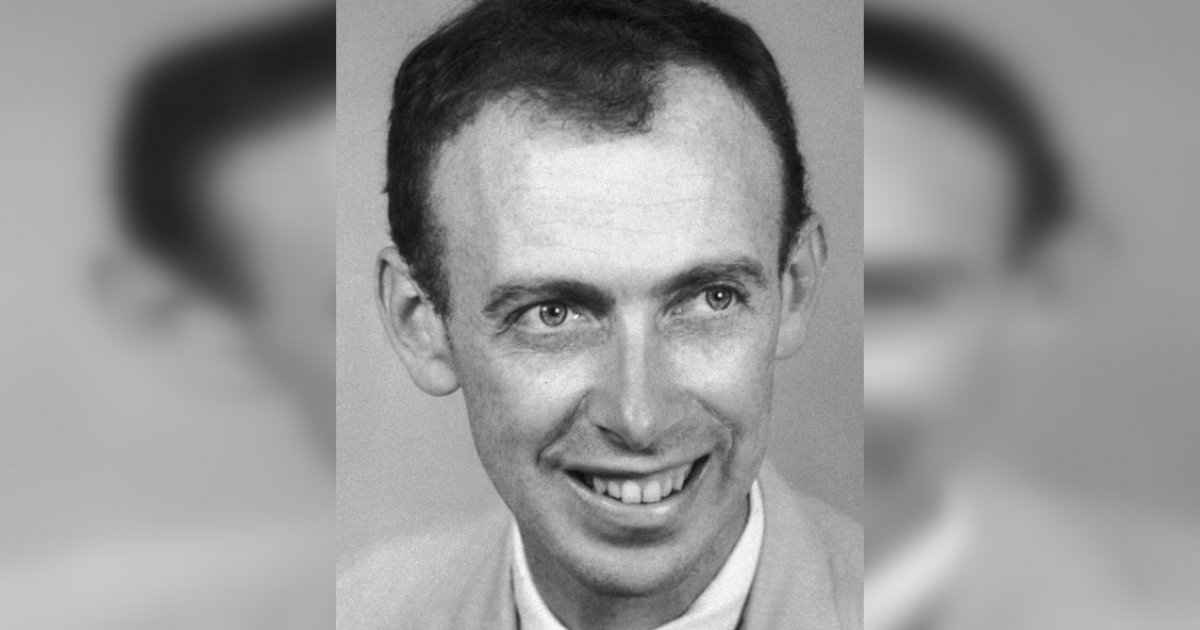

Dr James Dewey Watson is a legendary figure in modern biology. In 1953, he and Francis Crick opened a new horizon in the history of science by discovering the double-helix structure of the DNA molecule. In recognition of this groundbreaking discovery, he, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. His work was so fundamental that it is often described as the beginning of the modern age of biology. He was born on April 6, 1928, in Chicago, USA, and died at the age of 97 on November 6, 2025, in East Northport, New York.

Today, the world of science bids farewell to Dr James D Watson. He was one of the pioneering minds behind the discovery of the DNA double-helix structure, which permanently changed the course of biology and medicine. However, Watson’s influential life of 97 years was not limited to the brilliance of scientific success. His controversial remarks and ethical stances repeatedly called his extraordinary legacy into question. Nevertheless, James Watson, or “Jim,” remains an extremely influential and significant scientist of the century. His impact on the development of human civilization and the future of science will continue to be widely discussed and debated. With deep respect for the work of this great scientist, this article highlights James Watson’s major contributions to science and examines some of his controversial statements and ethical positions.

From an early age, James Dewey Watson was interested in science and the liberal arts. He grew up on the South Side of Chicago and attended South Shore High School. As a precocious student, he was a contestant on the 1940s radio series “Quiz Kids.” Due to the liberal policies of Robert Hutchins, he was admitted to the University of Chicago at the young age of 15. It was there that he encountered a popular science book about biology written by quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger. The book, What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell, confirmed for the young Watson that genes were the fundamental components of the living cell. He received his Bachelor’s degree in Zoology in 1947.

After graduating in 1947, he went to graduate school at Indiana University, where he met two legends in the field—Herman J Muller (who won the Nobel Prize in 1946) and Salvador E Luria. Dr Watson received his doctorate in 1950 under the supervision of Dr Luria. He then traveled to Cambridge—and toward fame.

One of the most important chapters of his career began at the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University, where he met Francis Crick. At just 25, Watson and Crick proposed the elegant double-helix model of DNA. They jointly published a groundbreaking, single-page research paper titled “A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid” in the journal Nature on April 15, 1953—a date now celebrated annually as World DNA Day.

They proposed that DNA is shaped like a twisted ladder, whose outer “rails” are made of sugar and phosphate molecules. Each rung of the ladder is formed by two of the four chemical bases of DNA: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. Adenine always pairs with thymine, and guanine always pairs with cytosine. They explained that enzymes inside the cell can cut this twisted ladder down the middle and use bases inside the cell to create two new DNA molecules from one. This discovery revealed how genetic information is encoded, replicated, and transmitted. It opened a new dimension in biology, enabling an understanding of genetic inheritance, protein synthesis, and revolutionary developments such as monoclonal antibodies for cancer treatment. For this discovery, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. Their findings laid the foundation for modern genetics, genomics, and computational biology. At the time, they famously said, “We have discovered the secret of life.”

Although DNA was discovered in 1869, scientists learned that it forms the genetic material of cells only in 1943. Still, the structure of DNA remained a mystery until 1953. Watson’s discovery paved the way for technologies such as identifying disease-causing genetic mutations, engineering genetically modified crops (GM crops), and today’s highly precise genome-editing techniques like CRISPR-Cas9. Jim’s contribution to laying the foundations of the ongoing revolution in industry, medicine, and agriculture—through genomics, genome editing, systems biology, and the application of artificial intelligence to the code of life—is unforgettable.

Dr Watson eventually moved from Cambridge, England, to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he accepted an appointment as an Assistant Professor of Biology at Harvard in 1955. He had a sharp eye for talent among undergraduate and graduate students and helped many of them, including several women such as Dr Hopkins, launch notable research careers. According to Dr Hopkins, Dr Watson was an inspiring teacher, although he tended to mumble at the blackboard with his back to the class. She said, “It was a lot of fun to be with him,” but noted that “he was easily annoyed, and if annoyed he would turn and walk away mid-sentence.”

From 1956 to 1976, he advanced molecular biology research in Harvard University’s Biology Department. Beginning in 1968, he spent nearly 35 years as Director, President, and Chancellor of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), playing a key role in elevating the institution’s funding and scientific output to world-class levels. Dr Watson first visited CSHL in 1948 for meetings with colleagues on bacteriophage genetics. When he was appointed to lead the institution in 1968, the lab had lost much of its earlier reputation. Bruce Stillman, President of CSHL, evaluated Watson’s work by stating, “The explanation of the double-helix structure is one of the three greatest discoveries in biology, alongside the discoveries of Mendel and Darwin.”

After discovering the structure of DNA, Watson wrote the molecular biology textbook Molecular Biology of the Gene (1965) and his bestselling book The Double Helix (1968), which highlighted his personal experiences and conflicts. The book was immediately acclaimed as a classic in science literature. The Library of Congress placed it on its list of America’s most important literary works.

Watson is known not only for the discovery of DNA’s structure but also for his role in initiating and advancing the Human Genome Project (HGP). He was instrumental in establishing the project between 1988 and 1992, and the full mapping of the human genome was completed in 2003. In 2000, a “working draft” containing the three billion letters of the human genetic code was completed. This achievement was celebrated in televised announcements from the White House by President Bill Clinton and from 10 Downing Street by Prime Minister Tony Blair.

Dr Watson left the project in 1992 due to disagreements over the patenting of genes. He was strongly opposed to patenting the blueprint of life. One of his sons was diagnosed with schizophrenia at a young age, which further motivated Watson to pursue genetic research in the hope of helping him.

In sharp contrast to James Watson’s—Jim’s—scientific brilliance are the serious ethical questions and controversial remarks that marred his public image. In explaining the structure of DNA, Watson and Crick used data and concepts collected by Rosalind Franklin and her colleagues at King’s College London. It is widely alleged that Watson and Crick used this data—particularly Franklin’s “Photo 51” and her research progress reports—without her permission or proper acknowledgment. Franklin was not eligible for the Nobel Prize because she had died of ovarian cancer four years earlier at the age of 37. In The Double Helix, Watson portrayed Franklin negatively and downplayed her contributions. His misogynistic treatment of Franklin raised deep questions about his ethical stance in science and society.

Watson’s acclaimed life was further tarnished by racist and classist remarks. In 2007, he told London’s The Sunday Times Magazine that he was “inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa because all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is not the same as ours.” He insisted that differences in average IQ between Black and White populations were due to genetic causes. Following these comments, the CSHL Board of Trustees suspended him in 2007, and he resigned as Chancellor. When he repeated his racist views in a 2019 documentary, CSHL revoked all his honorary titles and severed all ties with him. The institution called his comments “reprehensible” and “unsupported by science.” Such total isolation of a scientist from an institution he helped build is rare and unprecedented.

In addition, Watson advocated for genetic “treatment” of personal characteristics such as obesity and beauty. He once said, “Whenever you interview fat people, you feel bad because you know you’re not going to hire them.” These statements sparked widespread global condemnation. Claiming that the controversies had made him an “unperson” and hoping to raise funds for research, Watson auctioned his Nobel medal in 2014. He was the first living Nobel laureate to do so. The medal was sold for $4.8 million. In an unexpected gesture, the buyer—Russian billionaire Alisher Usmanov—later returned the medal to Watson.

When judging James Watson, a sharp dichotomy emerges between his monumental scientific contributions and his deeply flawed ethical conduct. He was one of the architects of modern genetics, whose work forever changed the course of medical science and biology. Yet his arrogant, controversial, and especially discriminatory comments about race and gender were harmful to society. His remarks are seen as a reprehensible effort to use science to legitimize social inequality.

Watson’s life shows how an individual can reach extraordinary heights in science while failing profoundly in ethical responsibility. James Dewey Watson will remain immortal as the co-discoverer of the DNA double helix. But it is impossible to judge his legacy solely by scientific achievement. A scientist’s social responsibility, ethics, and humanity are also part of his overall legacy. Modern science must learn from Watson’s mistakes so that ethics and empathy are never sacrificed in the pursuit of excellence.

(Tofazzal Islam is a Professor and Founding Director, Institute of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering, Gazipur Agricultural University and Fellow, Fulbright, Bangladesh and the World Academy of Sciences)