James Dewey Watson, the man who played a pivotal role in decoding the molecular structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), the substance that forms the basis of heredity, died on November 6, 2025, at the age of 97 in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, USA. Watson’s 1953 discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA not only earned him a Nobel Prize seven years later but also revolutionized the field of genetics and transformed modern biology forever.

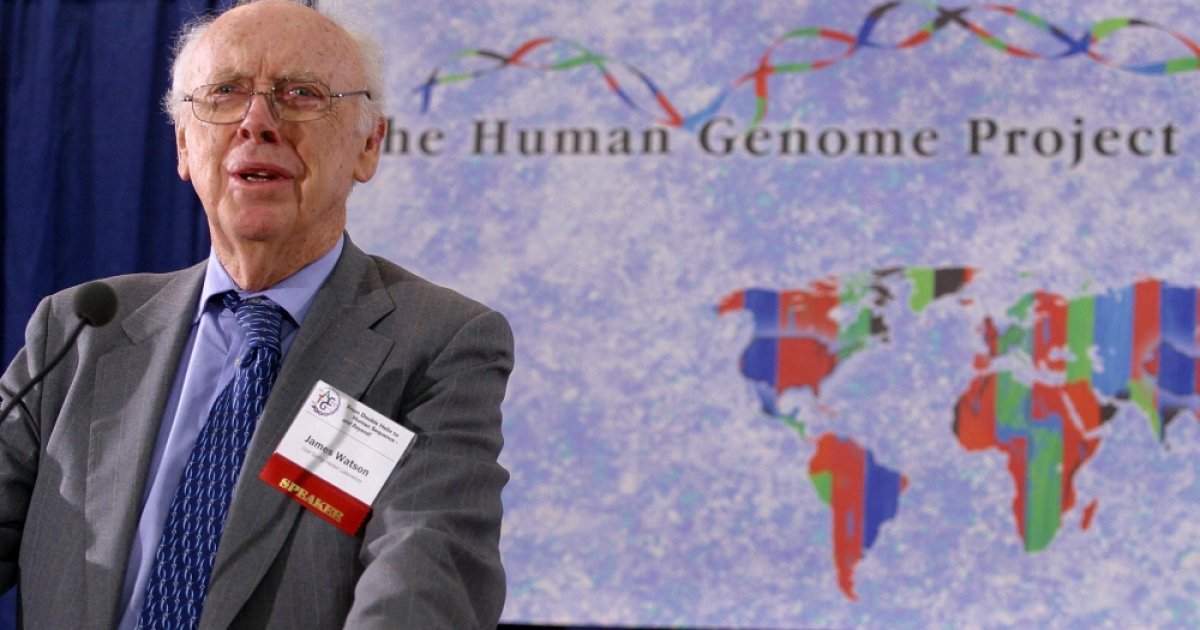

Years later, American geneticist and biophysicist James D. Watson would involve himself in one of mankind’s biggest, costliest, and most provocative biomedical research projects in history—the Human Genome Project. Watson was selected to lead the project, which began in 1990 with the goal of mapping all the genes in the human body. However, he resigned in 1992 due to a disagreement with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) over patenting specific DNA sequences. He strongly advocated for free public access to all genome data and opposed the patenting of DNA sequences, arguing they should be freely available to the public.

Born James Dewey Watson on April 6, 1928, in Chicago, Illinois, USA, he earned his PhD in Zoology from Indiana University in 1950.

James Watson’s scientific achievements are numerous, but he is best known for his collaboration with Francis Crick, which led to the 1953 publication in Nature revealing the molecular structure of DNA. For this groundbreaking discovery, Watson, along with English molecular biologist Francis Harry Compton Crick and New Zealand-born British biophysicist Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962.

Scientists from many countries, representing several scientific disciplines, were trying to understand the mysteries of life and heredity in the decades around 1900. Studying organisms ranging from grasshoppers to bacteria, they made new discoveries about the chemistry of living cells and the transmission of hereditary information. By the 1950s, many scientists were convinced that the particles carrying this information from one generation to the next were made of DNA, and several began attempting to unravel its chemical structure. The work of Watson and Crick, among others, ultimately contributed to the 1953 announcement that DNA was a double helix.

As the Nobel Prize committee later recognized, knowledge of the double helix held immense “significance for information transfer in living material.” Understanding the molecule’s structure helped explain how it could copy itself, passing on instructions from one generation to the next.

James D. Watson’s legacy is complex—marked by his co-discovery of the DNA double helix but also overshadowed by controversies and racist remarks he made in later years. Despite his early contributions, his later career was marred by widely criticized comments about race and intelligence, which led to his suspension and the stripping of his honorary titles from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Watson married Elizabeth Lewis in 1968. Together, they had two sons, Rufus and Duncan, and shared a life deeply rooted in science and education. Elizabeth, an alumna of Harvard University, was an active supporter of Watson’s scientific and academic endeavors.

Beyond his Nobel-winning work, Watson had a distinguished career as an educator, author, and science administrator. He taught at Harvard University from 1956 to 1976, where he inspired generations of molecular biologists. He later served as Director—and subsequently President—of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, transforming it into one of the world’s leading centers for genetic research.

Watson authored several influential books, including The Double Helix (1968), a candid and sometimes controversial memoir detailing the race to uncover DNA’s structure. The book remains one of the most widely read scientific autobiographies of the 20th century.

His other works include Molecular Biology of the Gene and DNA: The Secret of Life, both of which shaped science education worldwide.

Over his lifetime, Watson received numerous honors and awards, including the Copley Medal from the Royal Society, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the National Medal of Science. Despite the controversies that marked his later years, his scientific contributions remain foundational to molecular biology, genetics, and biotechnology.

Watson’s legacy lives on through the institutions he led and the countless scientists inspired by his discoveries. His lifelong fascination with the genetic code reshaped humanity’s understanding of life itself—from the structure of DNA to the vast frontier of modern genomics.

He is survived by his wife, Elizabeth Lewis Watson, and his sons, Rufus and Duncan Watson, who continue to uphold his commitment to education, inquiry, and scientific discovery.

(Ashiana Reaz is a biochemistry and biotechnology graduate and a contributor to Dhaka Tribune)