Wrongfully convicted of a crime he did not commit, Sanaullah spent 10 years on death row.

Protesting his innocence was a futile exercise since a confession was extracted under duress, leading the hapless man to end up in the condemned cell.

Sanaullah is now out of prison, a free person, but free only in the eyes of society, because in his mind, he is a prisoner with a noose hanging over his head.

The word “freedom” for a person who had spent time in the condemned cell carries complex and, often, morbid sub layers.

The time spent in solitary confinement left scars that will remain as long as he lives.

For too long, he passed each day with the shadow of death as a constant companion.

Living to him appears to be a surreal dream. In his own words: “I never want to remember my days in the condemned cell, those memories still haunt me; no one will ever understand what I went through.”

Sanaullah, and many like him, who were victims of wrongful convictions, spent a substantial period in the condemned cell before being acquitted.

Their tribulations and the silent ongoing battle to integrate into a society, which has a tendency to judge too quickly and harshly, form the basis of the profoundly touching exhibition titled: Living on Death Row: How People and Families in Bangladesh Cope with Long Term Solitary Confinement, currently ongoing at the Drik Gallery.

Supported by the Delegation of the European Union to Bangladesh, in collaboration with the Embassy of France in Dhaka and Drik Picture Library, this thought-provoking photo exhibition was inaugurated on October 10, 2025 to mark the European and World Day Against the Death Penalty.

The exhibition, containing photos by documentary photographer Mosfiqur Rahman Johan, presents a compelling narrative about people who spent time in the condemned cell, but after living with the spectre of death for many years, were finally declared innocent.

It highlights how wrongful convictions and inadequate access to justice continue to affect lives across Bangladesh, offering a deeply personal perspective on a global human rights issue.

One touching story is that of Majeda Begum from a village in Rangpur who was falsely implicated in the murder of a child in her village and was put in the condemned cell with her 13 month old son.

There, in that confined space, she raised her child, only to be released after six years.

Even more heart wrenching is the story of Sheikh Zahid, who spent 20 years in solitary confinement.

When he came out, the world had changed, the empty spaces he knew were now occupied by large buildings, a place he had once known appeared unknown.

Society had moved on. Zahid was left to feel like a misfit.

“Sometimes, when I lie down to sleep, I see a rope hanging above me; it feels so real that I cannot close my eyes, he says, adding: “The nights are long and the past never fades.”

Speaking at the opening ceremony, Ambassador Michael Miller, head of the Delegation of the European Union to Bangladesh said, “More than two-thirds of countries worldwide have abolished the death penalty in law or in practice, showing that justice and human dignity can prevail. Evidence shows that the application of the death penalty does not act as a deterrent to crime. It can risk, however, the execution of innocent people, as this exhibition well illustrates,” observed Miller.

Speaking at the exhibition opening, the French Ambassador to Bangladesh Jean-Marc Séré-Charlet recalled that France is at the forefront of the fight for the universal abolition of the death penalty.

“We remain committed to ensuring that justice repairs lives and does not destroy them. France will be the host of the next “World Congress Against the Death Penalty,” which will take place in Paris in July next year.”

After being released, Zahid’s greatest challenge was to fit into a society to which he was an alien.

In 20 years, the zeitgeist had gone through marked changes and many of the prevailing socio-cultural practices appeared a little puzzling.

Running a small shop, his life moves on and although the memories haunt him, Zahid often allows the gentle breeze touching his face to remind him that he is still alive.

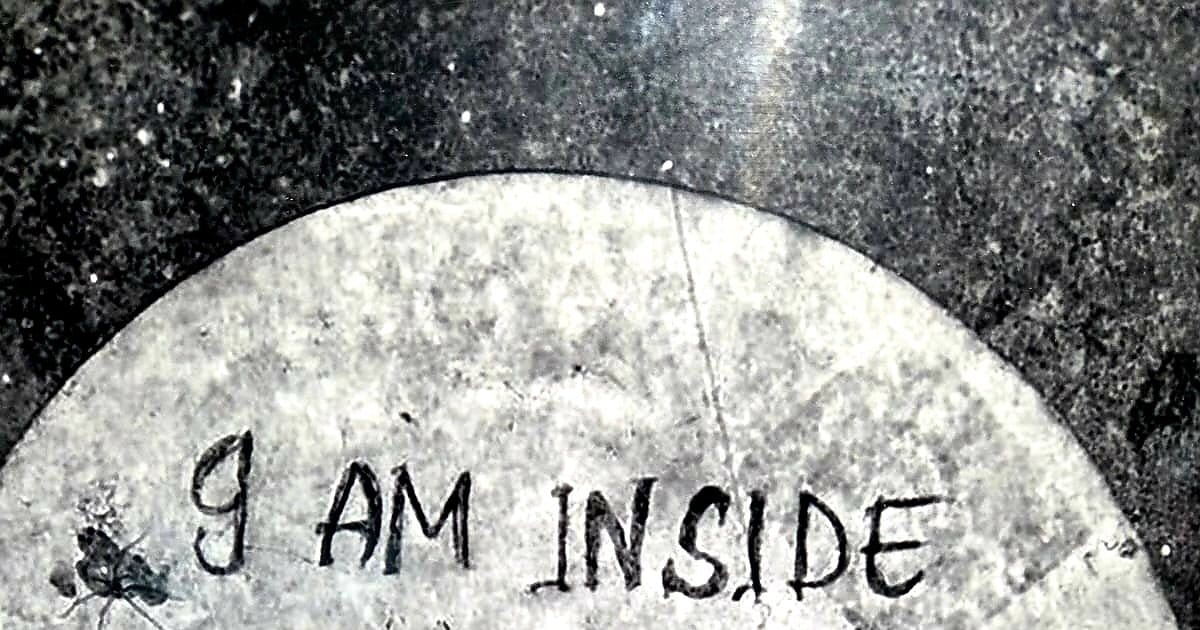

The stories of each victim, presented in detail through photography using light and shadow, have a common motif — loneliness.

Photographer Johan has captured through his works the quiet pain of each victim of wrongful conviction.

As most of them said, despite being proved innocent, the stain of conviction refuses to go away and thus, they slowly drift away to lead reclusive lives.

Sanaullah swimming in a pond, Zahid holding the photo that was taken the day he was taken to prison and standing alone by a stack of bricks on a desolate road as a free man, Majeda holding her son — all have a resigned despondence about them.

A stifled desperation masked by an unanswered question: Why?

They are breathing but the shadow of death has taken away their zest to be alive.

The exhibition is open to visitors till 19 October everyday 3-5 pm at Drik Gallery Dhaka.

Towheed Feroze is a former journalist.