For millions of women working in Bangladesh’s informal and marginalized formal economy, labour rights remain largely theoretical. Domestic workers without contracts, home-based garment workers invisible to regulators, tea-garden workers trapped in generational poverty, and fisherwomen excluded from official recognition continue to sustain the economy while remaining unprotected.

It is this contradiction—between contribution and exclusion—that brought women workers from tea gardens, fisheries, domestic work, and home-based garment production together in Dhaka on December 9, 2025, at the Informal & Marginalized Formal Women Workers Convention 2025. The gathering culminated in the announcement of a National Women Workers Forum, a landmark step towards unified representation in national policy spaces

Why the Convention Mattered

Bangladesh’s economy rests heavily on informal labour, much of it performed by women. Yet these workers remain excluded from labour laws, social protection systems, and national development planning. Fragmented struggles across sectors have yielded limited gains. The convention emerged from a shared realization: without a common platform, lasting policy change remains elusive.

The convention was jointly organized by four sectoral women workers’ networks—Bangladesh Nari Cha Shromik Jot, Domestic Workers National Forum, Women Home-Based RMG Workers Network, and Women Fisherfolk Network—bringing together voices that had long remained separated by sectoral boundaries national forum and its call to unite.

At its core, the convention was not just an event, but a political moment—aimed at building collective power, strengthening leadership, and establishing women workers as legitimate actors in national labour discourse.

EWCSA: From Isolated Voices to Collective Power

The convention was supported under the Empowering Women through Civil Society Actors (EWCSA) Project, a multi-year, multi-sectoral initiative.

The Empowering Women through Civil Society Actors (EWCSA) Project is co-funded by the European Union and implemented by Oxfam with 33 civil society partners in Bangladesh.

EWCSA focuses on strengthening grassroots civil society organizations, women’s rights organizations, and community-based groups so that women workers can organize, negotiate, and lead change themselves—rather than relying on charity or short-term interventions.

Operating across 20 districts in 8 divisions, 6 city corporations, and 32 upazilas, the project has reached 45,000 women workers in domestic work, tea gardens, fisheries, and home-based garment production.

Less than one percent of these workers previously had formal contracts, and most lacked awareness of labour rights or grievance mechanisms. EWCSA addressed this gap by building rights awareness, leadership skills, and collective organizing capacity.

From Organizing to National Visibility

EWCSA-supported networks have already delivered tangible results: domestic workers securing compensation in abuse cases, tea-garden women stepping into leadership roles, fisherwomen pushing for formal identification, and home-based garment workers engaging in wage and safety discussions.

Yet the convention acknowledged that gains remain fragile without structural reform. Participants emphasized that recognition under labour law, social protection coverage, and dignified working conditions cannot be achieved through isolated advocacy. A national platform was therefore essential.

The newly announced forum aims to consolidate women workers’ collective voice, ensure sustained engagement with policymakers, and press for long-overdue legal and institutional reforms.

Calls to Action: What Women Workers Demand

Drawing from the joint declaration of the convention, women workers issued clear demands—both immediate and long-term.

Immediate priorities include:

- Legal recognition of all women workers as “workers” under the Bangladesh Labour Act

- A national living wage framework for all four sectors

- Enforced occupational health and safety standards

- Immediate inclusion in national social protection schemes

- Zero tolerance for gender-based violence and harassment at workplaces

- Recognition of unpaid care work and access to childcare services

Strategic policy recommendations include:

- Establishing a government-recognized national women workers’ network

- Creating a digital national database and issuing work-based ID cards

- Ensuring women workers’ representation in all labour policy forums, with at least 33% participation

- Setting up a specialized legal aid cell under the Ministry of Labour

- Long-term public investment in leadership and skills development programs

- Developing a unified national policy framework for informal and marginalized formal sectors

A Shift in the Narrative

Speakers from government, civil society, academia, and labour movements echoed a common message: women workers must no longer remain invisible. Their labour sustains households, supply chains, and national growth—and their leadership is essential to building an inclusive economy.

As Bangladesh prepares for critical transitions in labour reform and development planning, the emergence of a national women workers’ platform marks a decisive shift—from fragmented survival to organized resistance, and from invisibility to leadership.

Experts laud initiative

Farida Akter, Adviser at the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock | “Women have always been a positive force in our society. Yet women workers remain deprived—both as humans and as women. In a patriarchal system, they face constant obstacles, and even our major economic assessments fail to recognize their contribution. When a person’s work remains invisible, it becomes a deep violation of human rights.” |

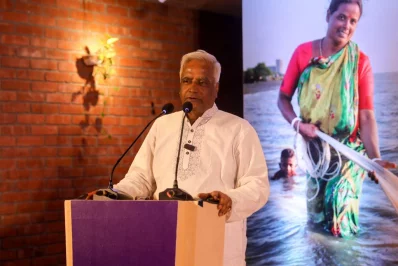

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed, Former Head of Labour Reform Commission | “From the tea gardens to the fisheries, our collective strength is our only path to recognition and justice. Women workers must be present where decisions are made, and the nation must acknowledge their labour as the backbone of our economy.” |

Ashish Damle, Country Director of Oxfam in Bangladesh | “This convention shows what becomes possible when women organize, speak, and lead. Bangladesh’s development journey must recognize and protect the rights, dignity, and leadership of informal women workers.” |

Laila Jesmin Banu, Program Manager for governance and human rights for the European Union Delegation in Bangladesh | The EWCSA initiative is powerful because it transforms both systems and lives. Its impact is visible in the leadership, confidence, and collective organizing of women workers. We hope this momentum continues to shape inclusive, evidence-based policy reforms in Bangladesh.” |

Dr Snigdha Rezwana, Professor at Jahangirnagar University | “We need to revise social and institutional norms that influence labour identities. Bangladesh requires a centralized database of informal women workers to support planning, service delivery, and legal reforms.” |

Mahmuda Sultana, Program Director at Oxfam in Bangladesh | “Women workers’ capacity were strengthened to recognize and claim their rights as well as to support each other.Raising their voice will enhance their collective bargaining capacities. Though legal and policy framework recognize some rights of women workers, implementation of those still remaininadequate.” |

Md Abul Hossain, Coordinator at Domestic Workers Rights Network (DWRN) | “There should be no discrimination between formal and informal workers. I support the formation of a women workers’ federation, which could elevate their collective bargaining at a national level.” |

Razekuzzaman Ratan, Former Member of the Labour Reform Commission | “Women workers, especially informal workers, had worked very hard to break barriers and come this far. They have caused significant stir in society.” |

Taslima Akter, President of the Trade Union Federation | “Out of 75-80 million workers in the country, only 15 million were formal workers, while the others were informal and out of the government’s support system. But recognizing domestic workers as informal workers has been a step in the right direction” |

Fawzia Khandker, Executive Director, Pragroshor | “Our achievements are not small, but more can be done collectively. While divisions are still there, we must raise our voices to demand our rights as workers. If we can unite, it would bolster accountability of policymakers.” |

AKM Ashraf Uddin, Executive Director of the Bangladesh Labour Foundation | “Support for informal workers needed to increase; otherwise, it would be difficult for Bangladesh on its path to LDC graduation.” |

Anni Akter, Homebased RMG Worker, Karmojibi Nari | “Despite being an informal worker, we don’t even have work-based ID cards despite being an RMG worker. This lack of professional identity often causes us to suffer from social stigma.” |

Farhin Akter Khushi, Domestic Worker Leader, AVAS | “We can’t take leave of absences, while our employers even cut our salaries if we take any leaves. This is because we are unaware of our rights as workers. We demand contracts/appointment letters to recognize our work, like other male workers.” |

Sharmin Sultana Moushumi, Advocate Supreme Court of Bangladesh and Vice President of Labour Court Bar Association | “Women workers, especially informal and marginalized ones, do not know that legal aid is free for them at labour courts. We will continue to fight for their rights, and will try to expand their accessibility to legal support such as free hotline services.” |

Sumaiya Islam, Executive Director, Bangladesh Nari Sramik Kendra (BNSK) | “Our objective must be to address gaps persisting in policy advocacy. We must attain a common platform to continue fighting for the rights of informal and marginalized women workers.” |

Sunzida Sultana, Additional Executive Director, Kormojibi Nari | “Most women workers lack work-based ID cards, and suffer from low wages and labour rights. For tea workers, it expands to workplace harassments – mostly physical and sexual. There is no healthcare benefits, or even child daycares at tea gardens.” |