Tobacco industry interference has intensified worldwide and remains deeply entrenched in Bangladesh, with a new global index warning that weak safeguards, opaque interactions, and tax policy concessions are undermining efforts to reduce tobacco use and protect public health.

The Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2025 urges governments, including Bangladesh’s, to adopt whole-of-government rules that keep the industry away from policymaking processes, increase transparency, and end political and financial dependence on tobacco companies.

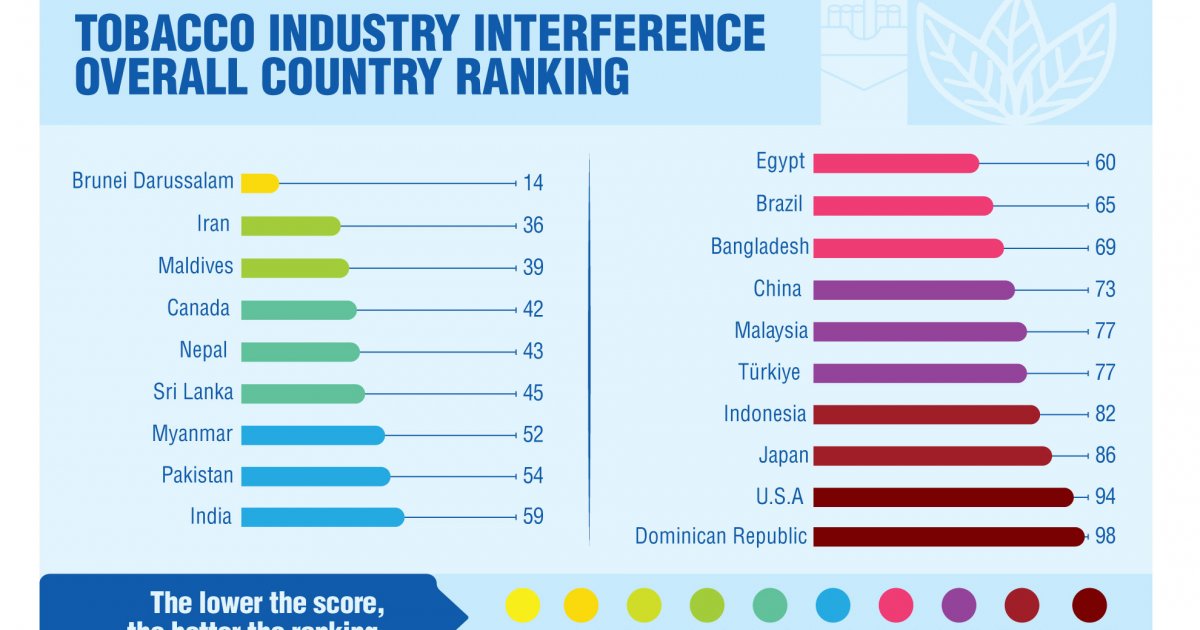

The Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2025, produced by the Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control in mid-November, assessed how 100 governments are implementing Article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which requires health policies to be protected from commercial and vested interests.

Almost half of the countries surveyed (46) saw their scores deteriorate over the last review period, largely because officials continued to allow industry input in lawmaking, accepted donations, or partnered with tobacco companies on enforcement and corporate social responsibility (CSR) projects.

At the same time, 34 countries improved, typically by adopting new codes or legislation aligned with Article 5.3, rejecting tobacco industry collaborations, and making interactions more transparent—such as publishing records of meetings and tightening lobbying rules.

However, the report concludes that overall the tobacco industry has become more aggressive in exploiting policy gaps, particularly in non-health ministries, by lobbying parliamentarians, ministers, and even heads of state to delay or weaken tobacco control measures.

Bangladesh is ranked in the mid-to-high interference band, reflecting persistent tobacco influence across policy development, CSR activities, incentives, and unnecessary engagement with senior officials.

Although the country registered a modest improvement compared to its 2023 score, the report shows that interference remains widespread and that Article 5.3 protections are still not fully implemented beyond the health sector.

In the detailed country scoring tables, Bangladesh records problems in several areas, including officials accepting industry assistance on enforcement, delays in implementing regulations following industry requests, and the continued visibility of tobacco-linked CSR activities endorsed by public agencies.

The index notes that, despite being a Party to the WHO FCTC, Bangladesh has not translated existing guidance on limiting interactions with tobacco companies into strict, enforceable rules across key ministries such as finance, commerce, and agriculture.

The 2025 index identifies Bangladesh among at least 10 governments—alongside Argentina, Bulgaria, Georgia, Israel, Lebanon, Poland, Sweden, Tunisia, and Ukraine—that delayed or failed to raise tobacco taxes after industry pushback, despite strong evidence that higher prices are among the most effective tools to reduce consumption.

Specifically, the report notes that no new taxes were imposed on bidis in the FY2024–25 budget, with authorities opting to maintain previous rates rather than introducing real increases that could curb use.

This tax stagnation followed targeted lobbying. In April 2024, the Pabna Bidi Factory Labourers Association submitted a memorandum to former prime minister Sheikh Hasina through the district administration, demanding the withdrawal of bidi taxes—effectively prioritising relief for manufacturers over improved protections for workers.

Public health advocates quoted in the report argue that such concessions signal to the industry that economic arguments can override health evidence. They warn that Bangladesh is missing a key opportunity to align fiscal policy with its tobacco-free commitments.

The index documents how tobacco-related CSR continues to serve as a powerful gateway to high-level decision-makers in Bangladesh and elsewhere, even though Article 5.3 guidelines call for such activities to be banned and denormalized.

Across the sample, governments were found to accept donations for education, disaster relief, or environmental projects, with ministers or local officials often appearing at events, cutting ribbons, and publicly thanking tobacco companies.

In Bangladesh, the report highlights that the commerce minister publicly presented British American Tobacco Bangladesh with an award for “Best Presented Annual Report,” a gesture the authors say confers state-backed prestige on a company whose products undermine public health goals.

The index also notes that a Bangladeshi diplomat in Tokyo met a Japan Tobacco International (JTI) delegation in 2024 and endorsed its ongoing business in Bangladesh—another example of diplomatic resources being used in ways that conflict with FCTC obligations.

One of the starkest findings for Bangladesh is the persistence of conflicts of interest involving senior officials and tobacco companies.

The report cites a case in which an additional secretary in the Ministry of Finance, Shirajun Noor Chowdhury, simultaneously served as a non-executive director on the board of BAT Bangladesh, creating a direct overlap between fiscal policymaking and the corporate governance of a major tobacco company.

Globally, the index records at least 17 countries where former officials moved into industry posts or industry executives were appointed to senior government roles. It singles out Bangladesh as an example where overlapping roles occur without clear cooling-off periods or conflict-of-interest rules.

The authors warn that, without strict prohibitions, such arrangements allow tobacco interests to influence decisions on taxation, investment, and regulation from within the state apparatus.

Across the 100 countries surveyed, most governments still lack comprehensive registers of tobacco industry lobbyists, clear disclosure rules for meetings, or public reporting of political and financial ties to tobacco companies.

The index shows that only 14 countries have general lobbying registers, and even in those cases tobacco-linked organizations and front groups are not always required to disclose funding sources or activities.

Bangladesh scores poorly on transparency, with no dedicated public register of industry interactions and limited publication of minutes or correspondence related to meetings with tobacco companies or their affiliates.

According to the report, this opacity allows lobbying to take place through informal channels—such as trade bodies, labour associations, or CSR partnerships—making it difficult for citizens, journalists, and civil society to track and challenge undue influence.

Alongside documenting interference, the index highlights governments that have taken decisive steps to protect health policy from tobacco influence.

Peru is cited as the latest country to incorporate Article 5.3 directly into national law, joining Botswana, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chad, Ethiopia, Gabon, Lao PDR, Nepal, and Uganda in adopting legislative provisions that bar industry participation in policymaking and establish penalties for non-compliance.

The report also notes that 32 countries have banned tobacco-related CSR, more than 20 have prohibited tobacco donations to political campaigns, and 46 have banned e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products—measures that collectively “denormalize” the industry and reduce its leverage over policymakers.

In some cases, customs and tax authorities have terminated memorandums of understanding with tobacco companies on illicit trade enforcement, replacing them with arrangements consistent with the FCTC Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products.

For Bangladesh, the Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2025 serves as both a warning and a roadmap.

On the one hand, the country’s score shows that parliament, the executive, and diplomatic services continue to engage with tobacco companies in ways that blur regulatory boundaries—from tax decisions and CSR endorsements to awards and high-level meetings.

On the other hand, the index’s recommendations outline concrete steps Bangladesh can take to align with international best practice and its tobacco-free 2040 target.

Key actions suggested for all governments, and particularly relevant for Bangladesh, include adopting a whole-of-government law or binding code on Article 5.3 covering parliamentarians, ministers, diplomats, and senior civil servants; prohibiting all political and charitable contributions from tobacco companies and their front groups; requiring full disclosure and publication of any official interaction with the industry; and ending incentives, awards, and CSR partnerships that grant the industry legitimacy or privileged access.

The report further recommends that governments levy the industry for environmental harms, reject industry-led clean-up campaigns, and ensure that the costs of waste and pollution are borne by tobacco companies rather than communities or public budgets.

The index concludes that, while tobacco industry interference has intensified, the experience of 18 countries that have strengthened Article 5.3 safeguards shows that such influence is neither inevitable nor insurmountable.

It stresses that only cohesive government action—treating the tobacco industry as a vested interest incompatible with public health rather than as a development partner—can prevent lobbying, CSR, and conflicts of interest from undermining life-saving policies.

For Bangladesh, where tobacco remains a major contributor to non-communicable diseases and premature deaths, the coming budget cycles and legislative reforms will test whether officials are prepared to move beyond statements of intent and adopt robust, enforceable protections against industry interference.