Every December 14, Bangladesh remembers its murdered intellectuals.

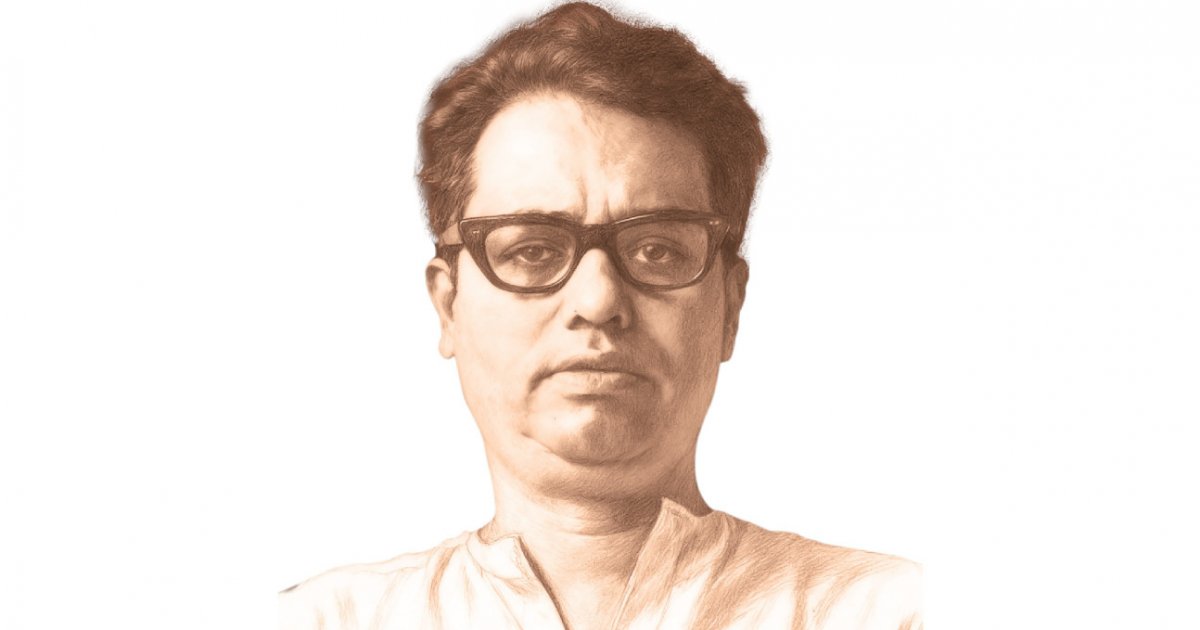

Among them, one name still echoes through the nation’s cultural memory: Professor Munier Chowdhury – playwright, teacher, critic, and one of the most hunted voices of his generation.

More than fifty years later, his family still stitches together his story from his wife’s memories and a country’s collective sorrow.

If there was a list of people the Pakistani rulers feared most, Munier Chowdhury’s name had been on it since 1948.

When Urdu was declared the sole state language, he openly protested.

His writings, his stage work, his activism – everything about him defied the state’s attempts to silence Bangla.

From that moment on, he lived under suspicion.

By the time the Liberation War broke out, he was already a political target.

Chowdhury – born in Manikganj in 1925, raised in a well-known Noakhali family – walked into Dhaka University in the late 1940s and quickly became one of its brightest minds.

He moved from the English Department to Bangla, won the Bangla Academy Award in 1962, and wrote plays that reshaped modern Bengali theatre.

Roktakto Prantor, Kabar, Chithi, Keu Kichu Bolte Pare Na – his works were not just literature; they were acts of resistance.

The day Al-Badr came

December 14, 1971. Noon.

Dhaka was on the brink of liberation. Pakistani soldiers were retreating. Rumours of freedom buzzed through the air.

At Chowdhury’s residence on Central Road, he was preparing to eat when a group of young men arrived.

No uniforms. No Pakistani soldiers.

Just Bangalees, around 20 to 25 years old, wearing identical ash-coloured shawls.

At first, nothing seemed alarming.

Then one of them placed a gun against his back.

They led him outside. That was the last moment his family ever saw him.

He never returned.

He was almost certainly killed the same day, one more victim of Al-Badr’s coordinated slaughter of the country’s brightest minds.

His body was never recovered.

A son raised by memories

In an interview with Dhaka Tribune, Chowdhury’s youngest son, Asif Munier (Tonmoy), now an activist and writer himself, said he remembers nothing of his father except the stories his mother preserved for decades.

“I was four. My mother carried the memory for us,” he said.

According to her, in those final days of the war, Chowdhury was filled with hope.

He would sit by the radio listening to the BBC and repeatedly tell her: “Lily, it’s only a matter of days. The country will be free. There is nothing to fear now.”

She believed him, until December 14.

During 1971, the Chowdhury family moved from place to place – from the teacher’s quarters in Nilkhet to Hatirpool, then finally to Darul Afia.

They lived through the horrors of March 25, the crackdowns at Dhaka University, and the everyday fear of being watched.

A nation’s loss that never heals

Chowdhury knew he was a target.

He had already been jailed twice – once in 1945, and again for three years during the Language Movement.

But his belief in a secular, democratic Bangladesh kept him working, writing, and teaching, even as danger closed in.

“Perhaps we never fully knew who my father was,” Tonmoy said, “but the men who came for him certainly did.”

Like countless intellectuals murdered in those final hours before victory, Chowdhury was killed to cripple Bangladesh’s future – an attack on the nation’s brain, not just its body.

Today, as Bangladesh observes Martyred Intellectuals Day, grief still runs parallel to victory.

The country celebrates the freedom won in 1971, but the absence of voices like Munier Chowdhury’s remains an unhealed wound.