The War of Liberation and the way Bangladesh observes and celebrates Victory Day on December 16 1971 is a historical truth that will, forever, define the core values of a Bangladeshi — today, tomorrow and in the days to come.

Just like now, fifty-four years later, back in the first decade after independence, Muktijuddho played a pivotal role in the socio-political ethos of the country.

Its spirit was present in the everyday struggle in a country that was desperately poor, ravaged by natural disasters and famine, wracked by relentless political intrigue and often ended up on the verge of total catastrophe.

Yet, Bangladesh never imploded as many had cynically prophesied in the 70s.

From a hard-core financial aspect, in the first and the second decades after independence, Bangladesh, on one hand was trying to attain a sense of stability in all sectors and, on the other, retaining the pride of 1971.

While today, the celebration for Victory Day and the days leading up to December 16 carry distinct air of bullish optimism, in the 70s and 80s, the spirit of 1971 was laced with stoicism and fortitude.

When ‘gondogol’ was a common term

For many of you reading this piece, the surprising thing will be the usage of the word ‘gondogol’ (troubles) which was widely used in the first decades after independence.

This term is no longer in use in any form.

But back in the first two decades, ‘gondogol’ was regularly used, especially in casual conversations.

The 1980 film Ghuddi, starring Raisul Islam Asad and Suborna Mostafa, available on YouTube, captures the post-independence malaise affecting the youth of the period.

In that film, during a conversation, 1971 is referred to with the term ‘gondogol.’

As a person who is just as old as Bangladesh, I have had the opportunity to see first hand the social evolution of this country.

And what a journey that has been!

To sum it up in one sentence — have seen the frugal life in Bangladesh and now marvel at the fabulous changes.

As young children and then as teens, we grew up in a time when almost everyone older than us from domestic help to teachers to relatives to guardians to random strangers on the streets had vivid memories of the nine-month war and, certainly, December 16.

It was a common family culture to sit around older relatives to listen with rapt attention as to where they were during the nine months and how they managed to deal with a plethora of challenges.

At school, teachers spoke of their experiences while around Dhanmondi the common December time discussion was about the dumping of weapons in the Dhanmondi Lake.

Text-books at school had several large chapters on our Independence although the most striking feature from that time is that no one ever tried to indoctrinate us with a one- sided politicised narrative of 1971 — something which we were faced with later in Bangladesh’s history.

Rampant manipulation of the history of 1971 was absent.

As far as I recall, we were taught about Muktijuddho and freedom fighters who fought to give us a free land and the right to act and think independently.

And we were taught about collaborators — those who opposed the war and the creation of Bangladesh.

Celluloid portrayal of 1971 was a regular feature:

In the 70s and 80s, both the small and the big screens presented films with the War of Liberation as the main theme.

From Ora Egaro Jon to Arunodoyer Agnishakkhi to Dhire Bohe Meghnato Ekattorer Jishu — a large collection of films ensured that sacrifices and valiant efforts of the freedom fighters are always in the public psyche.

Late Zafar Iqbal, the flamboyant debonair actor of the 70s and 80s, was also a freedom fighter along with Sohel Rana.

They were invited to TV programs to recount their experiences which added to their public appeal.

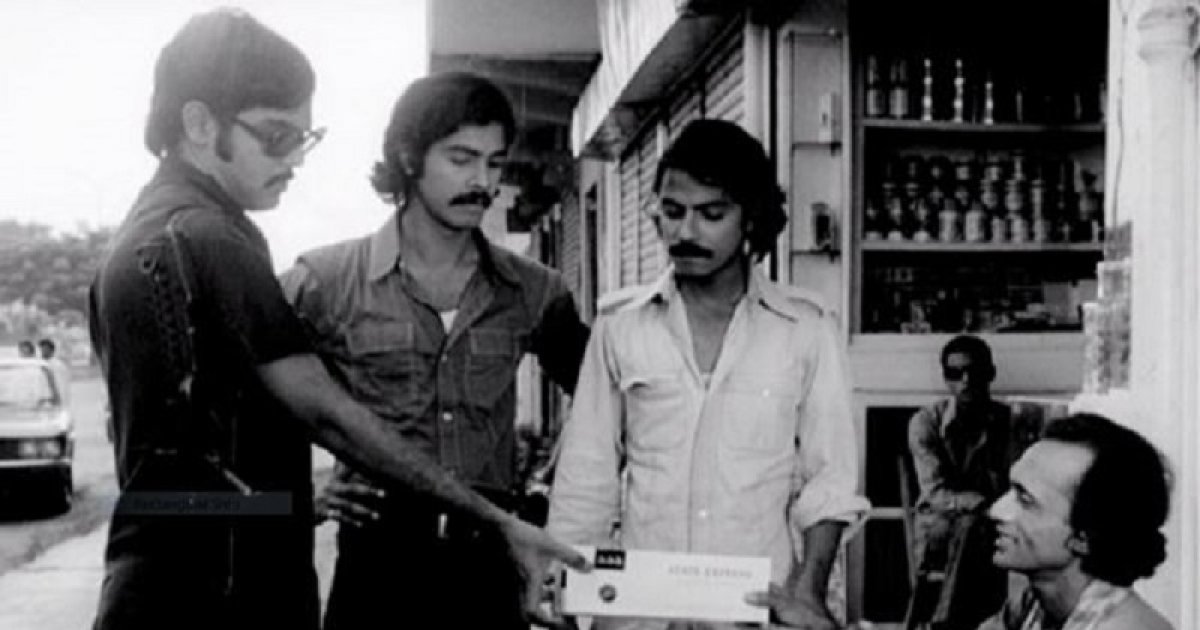

Another celluloid gem, which is not available on YouTube, is the movie by Khan Ataur Rahman: Abar Tora Manush Ho!

Speaking on this film, Faizul Bari, a political analyst plus a teacher, says: “This film carries historic and social value because it depicts the aberrations in a newly born nation.”

After Bangladesh emerged on the global map, the country became a focal point for a large number of international donor agencies and massive relief work, he said, adding: “However, at the same time, shady syndicates developed, unscrupulous traders began to hoard simple items like onions, oil while racketeering compounded the misery of the people who lacked basic amenities in a devastated country.”

“Abar tora Manush ho is about freedom fighters who did not submit their weapons, fighting another battle in a newly formed state against profiteers, corrupt officials and nepotism.”

Agreeing with Faizul, Anwar Hossain, a retired accounts official of a public university observed: “Abar Tora Manush Ho needs to be salvaged and shown because it’s not available in the public sphere.”

His belief is that freedom fighters fought two battles, one against an invading force and, another against local traders and corrupt politicians who exploited the post-independence despair.

In the 70s and 80s, there was another question which triggered hours of debate, and is not heard anymore: Shadhin hoya ki bhalo hoilo? (what good has independence brought us?).

Thinking back in retrospect, one feels that this question was never aimed to actually demean 1971 and the formation of a free nation but to vent the simmering frustration the common person felt at the volatile political scenario plus the austerity driven post liberation life where struggle was present in all areas of existence.

In fact, I saw those young men who often looked morose at the political turmoil affecting the fledgling country, beam with pride when December 16 came.

On that day, all misgivings were brushed aside, the red and green were flown high and the resolve in the eyes of all carried one message: We are Bangladesh and we will not fail!

Standing in 2025, with such a lot of achievement in all areas, I think of a line that we heard a lot in the 80s and dare to rephrase it differently: The basket was bottomless, but we made a bottom and stand on it now.

Towheed Feroze is a former journalist.