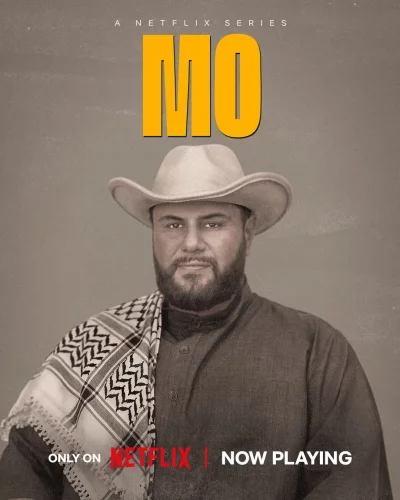

In a television landscape long haunted by caricatures and convenient villains, Muslim American comedian Mo Amer is doing something quietly radical: he is telling the truth as he knows it — loud, funny, bruised and human.

Amer’s Netflix dramedy Mo returned with a second season that doesn’t merely entertain; it unsettles.

It opens not with glamour but with absurd survival — its hero, Mo Najjar, flipping falafel tacos in Mexico after being caught in a van smuggling stolen olive trees across the US-Mexico border. It is comic chaos, yes, but also an aching metaphor for displacement, identity and a life forever stuck between checkpoints.

Written from Amer’s own lived experience as a Palestinian refugee, Mo refuses to sand down its edges.

The series traces asylum, detention centres, fractured families and the weight of geopolitics — without preaching, without begging for sympathy. That authenticity has paid off.

The first season won a Peabody Award; both seasons became Netflix hits. Amer’s third comedy special, Mo Amer: Wild World, dropped in October, further cementing his voice as one of the sharpest of his generation.

What makes Mo resonate is not just its politics but its intimacy. “Once you write honestly to your culture and story, others see themselves in it,” Amer says — and audiences clearly do.

The show ends before the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack, yet it never flinches from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or the psychological toll of being an asylum seeker in America.

Amer is not alone. A new wave of Arab and Muslim American creators is reshaping Western screens.

Muslim Matchmaker presents Muslim Americans not as headlines but as hopeful romantics. Ramy Youssef’s animated #1 Happy Family USA follows an Egyptian American family navigating post-9/11 paranoia with biting humour and tenderness.

For decades, Hollywood offered only extremes: bombers, billionaires or belly dancers. Before that, it was camels and harems — a colonial gaze that reduced entire cultures to spectacle. Scholars call it Orientalism. Audiences felt it as distortion.

These new shows flip the script. They show Muslims as neighbours, lovers, parents, messes — Americans with hyphenated lives and unresolved histories. And that matters. Studies show positive representation doesn’t just change hearts; it shifts attitudes toward policy and power.

Still, the fight is unfinished. Industry gatekeepers remain cautious, sometimes fearful of nuance. Amer knows this. His answer is simple and defiant: keep writing.

In a world addicted to labels, Mo insists on complexity. And that, perhaps, is its most revolutionary punchline.